FABULOUS FIGURES

Fabulous figures come in all sizes and at all price points. There is one for every pocket!

These figures are from various collections and not for sale. They appear only to share their beauty.

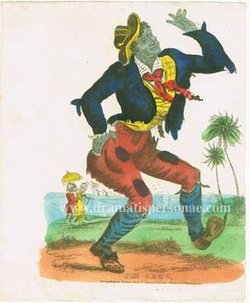

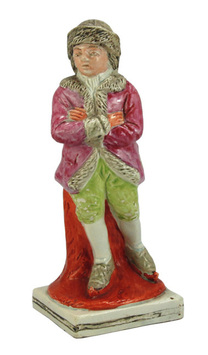

Jim Crow

Thomas Dartmouth Rice (1806-1860), the man who gave the world Jim Crow, was born and raised in New York. Trained as a woodcarver, he preferred the life of an itinerant entertainer. By 1826, he was earning his keep around America as a prop man and small-part actor. Between acts, he performed a shuffling, jiggling dance to the tune of a black American slave work song. The routine cruelly parodied the crippled movements of a slave named Jim Crow, who worked in the stables behind the theatre, although his limbs were gnarled with arthritis. Rice staged his Jim Crow routine in black face, thus creating a stereotype for black minstrelry that was to quickly become wildly popular.

Rice's debut as Jim Crow at the Adelphi Theatre in London on 7 November 1836 was so successful that other plays were adapted to create Jim Crow roles. Rice and Jim Crow became an international sensation. People of all classes capered to the ditty and printed images of Jim Crow proliferated.

Figures of Jim Crow are very rare. I have recorded only one other model (and only three copies of it). Staffordshire spelling was often erratic, but Jim was a contraction of James not in use in England at that time, and this probably accounts for the misspelling.

Vicar

Tithe Pig Group

Dr Syntax Stopped by Highwaymen

Doctor Syntax was a peripatetic clergyman who set off "in search of the picturesque"--finding pleasing vistas was an appropriately refined pastime in those days. Along the way, he has a series of adventures, which are portrayed in Rowlandson's illustrations. And this rare group titled Dr Syntax Stopped by Highwaymen mimics one of the book plates, titled Doctor Syntax Stopt by Highwaymen.

Dr Syntax Plays at Cards

This particular figure group was made circa 1825. H: 7-3/4”. It has an interesting recent history. It came to auction after being discovered in a garden shed in England in filthy but superb condition, probably because it had been saved from zealous domestic dusting.

A similar figure group in the Willett Collection, Brighton Museum, can be seen on page 193 of Schkolne, People, Passions, Pastimes, and Pleasures: Staffordshire Figures 1810-1835. Crude, modern renditions of this group abound. These were made in Asia, not Staffordshire, and appear frequently on eBay.

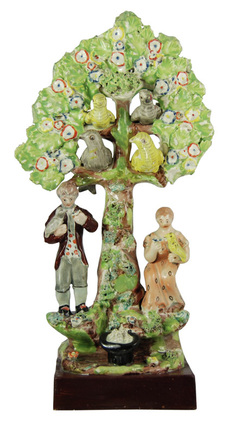

Bird Nesting Group

Girl with Doll

"Patriotic Group" Sheep

Our sheep have bright enamels and a glaze that glows. The big flower bocage has numerous indentations on the surface, so there is no large flat area coated with glaze to reflects light. Consequently, the bocage looks a little dry and is the perfect backdrop to allow the figures to sparkle. H: 5-1/4".

"Patriotic Group" Recumbent Sheep

Sherratt-style Recumbent Ram

Sherratt-style Recumbent Sheep

Bear Baiting Group

Bear baiting was a gambling sport that was at its height in the Elizabethan era. In fact, bear baiting was Queen Elizabeth I’s favorite ‘diversion’. The first theatres, built in Elizabethan times, were in the round because they were modeled after bear gardens. Some were dual purpose: a bear baiting one day and Shakespeare the next. Bears were not baited to death because they were valuable animals, but dogs frequently succumbed. By 1800, baiting sports were perceived as politically incorrect but they continued entertaining all echelons of society until 1835, when Parliament banned them.

Formerly with Manheim, NY, and in the Hope McCormick Collection. Exhibited at the Mint Museum of Art, Mirth & Mayhem: Staffordshire Figures 1810 -1835, Nov.206-April 2007. See also Schkolne, People, Passions, Pastimes, and Pleasures: Staffordshire Figures 1810-1835, p127 , and Manheim, Selections from the McCormick Collection of Staffordshire Pottery, plate 25.

Gardeners Bocage Group

Despite its seeming vulnerability, this figure is perfect. Not a nick. It is similar to the very attractive example of page 249 of Schkolne, People, Passions, Pastimes, and Pleasures: Staffordshire Figures 1810-1835. The owner traded that example for this, citing the broader taller bocage and the perfection, as reasons.

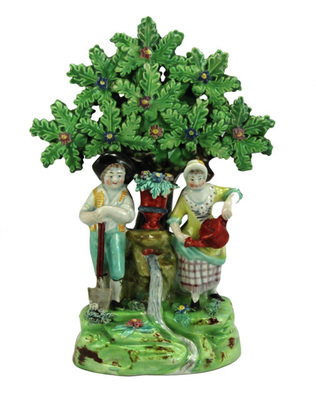

Pair of Agricultural Workers

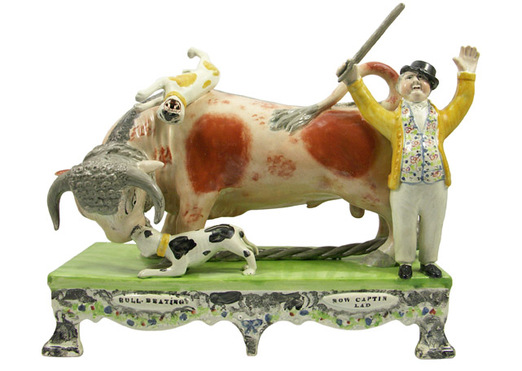

"Sherratt" Bull Baiting

|

Here we see an early 19th century bull baiting by Henry Alken. But above all, bull baiting evolved into a great gambling sport. Dog owners and spectators would wager on a dog’s abilities to pin the bull to the ground by the nose or lip, while the bull would try and toss the dog into the air. This brutal, vicious sport was beloved at all levels of society although it resulted in blood curdling injuries to the animals—and spectators often got caught in the fracas. In 1835, Parliament banned baiting sports.

|

This figure group is definitive of the “Sherratt” style. A bull baiting group like this was the first Staffordshire figure to earn a Sherratt attribution when Herbert Read, writing in 1929, commented on "the excellent bull-baiting groups...attributed to Obediah [sic] Sheratt." Mr. Read did not explain how he reached his conclusion, and 80 years later we are no nearer knowing whether Obadiah Sherratt did in fact pot the bull baiting group that catapulted him to fame! But we do know that Obadiah Sherratt potted in the early 1800s, even though the only wares bearing his name are two frog mugs. Despite this, many figures with a vigorous earthiness are traditionally attributed to Sherratt. There is no denying that these figures share common distinctive characteristics; they need to be called something, and the label “Sherratt” style recognizes that credit for this work may go to Sherrat—or to an unknown potter.

Today, we are fortunate in that distinct criteria for a 'Sherratt' attribution have been established in Malcolm and Judith Hodkinson's book Hodkinson, Malcolm & Judith. Sherratt? A Natural Family of Staffordshire Potters.

Beware small versions of these bullbaiting groups were made in the 20thCentury.

The following is from Oliver, Anthony,. Staffordshire Pottery: The Tribal Art of England. Page 45.

"These bull-baiting groups on both flat and table bases are still much sought after by collectors but do beware of a small one about 5 ¼ inches high and 7 ½ inches wide. It is nicely potted although the glaze and the colours are wrong for Sherratt. It was produced by the William Kent factory and was last quoted in their catalogue for 1960. Some years ago when I was doing some research in the Potteries, I spoke to the man who had reduced it in size and potted it for the Kent factory. He had one of them in a little cabinet in his living room and was very proud of it in his retirement".

Writing in 1981, Anthony Oliver went on to say that he had seen large amounts paid for these small groups by ignorant buyers. Sadly, the same remains true today! In addition, there are other small, crude models of more recent Asian manufacture.

The London Barber

Pair of Standing Sheep

Recumbent Ram

"Sherratt" Summer

Dixon Austin & Co, The Four Seasons

John Baker in his Bible on lustre, Old English Lustre Pottery, describes this set of Seasons as 'the most desirable examples of Sunderland pink lustred wares'. Few complete sets are documented. However, it seems these molds were used beyond the Garrison potbank for figures decorated without luster and for Pratt examples.

Wilson Four Seasons

Walton Four Seasons

Walton, Spring

Scrolling foliage has been recorded on no other Walton figure. It is a rare feature that has only been found on figures representing the Four Seasons. In all but one case, these figures are of the same form as the known Walton examples; however, they bear no mark or feature to facilitate attribution. A single figure of Winter, fashioned as a man wearing skates, has also been recorded with scrolling foliage.

Winter

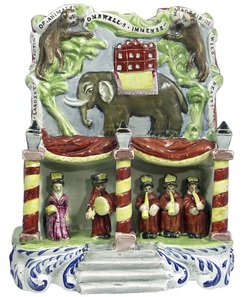

Wombwell's Menagerie

The menagerie shown here is in the collection of the Newcastle-under-Lyme Museum. While other menagerie forms are in the “Sherratt” style, this menagerie is not. It is conjectured that this menagerie was a precursor to the larger and later “Sherratt” menageries.

|

|

In 1805, young George Wombwell, then a cobbler bought two boa constrictors off the London dock and made so much money showing them that he was able to establish his own traveling menagerie. In the early 19th century, the opportunity to observe animal behavior appealed to people from all walks of life. Wombwell's was summoned to exhibit before royalty on several occasions. This was the era before photography and most people hadn't even seen a drawing of some of the menagerie's animal stars. For the average man in the street, the arrival of a menagerie in the village afforded opportunity to verify the existence of hitherto mythical beasts.

George Wombwell was the 19th century's ultimate menagerist. He died in 1850--by which time he had three menageries--but menageries bearing his name toured until around 1930. |

Dandy and Dandizette

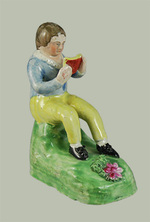

John Dale, Reading Boy

"Patriotic Group" Perswation

Courtship in the early 19th century was, for the better classes, a high stakes game that was primarily about money. At the same time, parents were increasingly reluctant to force their children into unacceptable marriages. So Persuasion was needed! For a long time, Jane Austen’s novel Persuasion, published in 1818, was thought to have inspired our earthenware Perswation group. Instead, a print, titled Persuasion and dated 1809, is clearly the figure’s design source. Dated design sources such as this print are invaluable in guiding the dating of our figures.

Cow with the Iron Tail & Blacksmith

The water pump itself was in the past known as “the cow with the iron tail” because water was commonly used to adulterate milk. Our pearlware figure of a girl at the water pump is is dubbed by collectors "The Cow with the Iron Tail". This figure is even rarer than good water was in its day. I know of a only a few examples. Two are in museum collections at Brighton and Hanley (see Schkolne, p174 for the former). I also recall a catalogue illustration of an example on a round base.

The design source for the figure was probably an engraving by William Henry Pynne, created for his subscription series publication, Microcosm, published from 1803-1806 (illustration reproduced in Schkolne, p174). Microcosm was a design source for transfer-printed pottery, so it is quite possible that figure potters used it too.

The figure of the blacksmith that accompanies our "Cow with the Iron Tail" is exceptionally rare. I know of only one other example and it was in poor condition. It sold in a London saleroom many years ago. I don’t know the design source for this figure, but perhaps it was simply inspired by an everyday scene.

Some of the finest early 19thC enamel-painted figures are on vermicular bases, such as those that support our blacksmith and his companion. Such figures are often carefully modeled and particularly nicely glazed and richly enameled. This pair is no exception. Who made them? We simply don’t know.

Cows Spill Holder

Who made this tour de force? We simply don't know. While the style is evocative of the work of Walton, a host of other potters used similar bocages and fashioned their wares in this style.

"Patriotic Group" Pair of Recumbent Deer

These deer are attributable to a pot bank dubbed 'Patriotic Group' . Our deer were gorgeous when they left the kiln and they have survived to this day in the same condition. The glaze glows, the enamels are bright and clear. Amazing that those tall antlers have not been nicked. The bocage looks a little dry and is the perfect backdrop to allow the figures to sparkle.

By the early 1800s, deer were no longer hunted and slaughtered. Instead, they were valued as adornments on the estates of the landed elite. When a deer hunt was staged, a deer was captured and carted to the hunt site. The animal was released for all to chase, but it was captured at day's end and returned to its park. Even then, the deer was recognized as too beautiful to kill. The plethora of deer wrought by Staffordshire's potters are a tribute to one of nature's most graceful creatures.

Thomas Cribb & Thomas Molineux

In 1810, Molineux challenged Cribb to a title fight. England’s attention was riveted on the Cribb–Molineux contest, for national self-esteem and identity were at stake. The Fancy, as boxing’s aficionados were called, wanted a white boxing champ. That Molineux was an American was hardly significant for, as the Sporting Magazine explained, “what alarmed the natives most was, the consideration that an African or a tawney Moor, was looking forward to the championship of England, and had even threatened to decorate his sooty brow with the hard-earned laurels of Crib. [sic]” On December 18, 1810, thousands of spectators braved torrential rain and waded through miles of knee-deep clay to reach the remote outdoor venue near East Grinstead where Cribb was to defend the national honor. The pugilists traded blow after blow in seemingly interminable rounds. Then around round twenty-eight—history has chosen not to record this accurately—Molineux felled Cribb. Clearly a black American was the new English boxing champ. But as Molineux claimed victory, Cribb’s second jumped forward, falsely charging that Molineux had held bullets in his fists. The resulting fracas gave Cribb time to recover and left Molineux shivering in the rain. When the fight resumed, Cribb outlasted Molineux, but only just. In round thirty-three, Molineux declared, “I can fight no more”—apparently, neither could Cribb. His claim to the English championship was validated, although its fairness could be questioned.

On September 28, 1811, Cribb answered Molineux’s challenge to a rematch at Thistleton Gap. By now the pugilists’ names were on every tongue, and even those who knew not the names of the great military heroes dying for England’s glory on the battlefields of Europe, knew of Cribb and Molineux. The motley crowd of twenty thousand that flocked to the remote field included peers and peasants, swells, and occupants of stews. But this time, Molineux did not stand a chance. While Cribb had spent eleven weeks training with the famous Captain Barclay at his secluded country estate, Molineux had been forced to earn his keep at local sparring matches. Both men had lost weight, but whereas Cribb had shed fat, Molineux had lost muscle. It took a mere eleven rounds, and nineteen minutes and ten seconds, for Cribb to knock out Molineux. The challenger was heaved out the ring with his jaw and ribs fractured.

Cribb’s victory was an event of national significance and he returned to London in a beribboned coach, cheered along its route in the manner accorded the bearer of news of a military victory. A huge crowd awaited him at his home and delivered a greeting worthy of a champion. Nationwide, fortunes had been made and lost on the fight, and the Edinburgh Star admonished the country for wagering more on its outcome than had been given to aid British prisoners in France. The Fancy found a defeated Molineux admirable, and he became a popular boxer of secondary standing, notorious for his love of ladies, liquor, and spiffy clothing. In 1818, emaciated and estranged from his friends, he died in Ireland. Although Tom Cribb never again defended his title, he reigned as a respected and beloved champion, the biggest sports star of his era, until he retired in 1821.

Our pearlware figures of Cribb and Molineux date from circa 1811. At 9" tall, they have an imposing presence. Such Staffordshire figures are particularly rare and capture a moment in sporting, social, and ceramic history that continues to enthrall. Staffordshire figures of Cribb and Molineux were made in the 1820s—probably around the time of the next great boxing contest between Spring and Langan in 1824—but the earlier figures are especially lovely.

Fascinating Factoids.

- Boxing champions of this era were England’s very first sport stars; hitherto only exceptional animals had been household names in the sporting world. Boxing (or milling, as it was commonly called) was patronized at the highest level of society, but it appealed to all classes because fights indulged the national propensity to gamble.

- Boxing matches were illegal in the early 19th century. The ideal site was a remote outdoor location that accommodated thousands of spectators and eluded magisterial detection.

- The boxing ring was a roped-off area, usually from twenty to forty feet square, and it was surrounded by an outer ring accessible only to umpires, officials, select friends, and those charged with keeping the crowd at bay. A sea of standing spectators surrounded the outer ring, and carriages and wagons circled the field to form a grandstand of sorts. Sometimes crowd control necessitated constructing an elevated wooden stage for the ring.

- Boxers did not wear gloves. Each boxer, stripped to the waist, was assisted by only his bottle-holder and his second. The latter lent his knee as a seat, offered advice, administered ringside surgery, and generally did whatever it took—biting ears was common—to keep his man conscious.

- Unlike today’s fights, matches were unlimited in length, and rounds ended only when a boxer went down. A downed boxer had a thirty-second count, and then he had to be at the scratch, the name given a square chalked in the ring center. If he could not make it, he was defeated. Fights were protracted slugfests in which men pummeled away at each other interminably. Blood flowed freely as bare fists shredded faces, swelled eyes shut, and reduced hands and knuckles to painful pulp, despite careful pre-fight “pickling” in astringent. Matches could last very many rounds, very many hours. Boxers fought relatively few times in their lives because the human body can only take so much.

Enoch Wood, Billy Waters

This Fabulous Figure depicts Billy Waters. It is 8" high, pearlware, made in Staffordshire circa 1822. The photo is provided by John Howard Antiques.

Billy Waters was a former American slave who served and lost his leg in the British navy. In the early nineteenth century, this peg-legged black busker known for his fiddle and beribboned cockaded hat was a familiar site in London’s theatre district. In 1819, Lord Busby’s Costume of the Lower Orders of London included a color lithograph of Waters, looking much as he does in the Staffordshire figure--and you see can it alongside our Fabulous Figure.

In November 1821, William Thomas Moncrieff’s burletta Tom and Jerry; or, Life in London, an adaptation of Pierce Egan’s book published earlier that year, opened at the Adelphi Theatre. Moncrieff introduced the character of Billy Waters into his play--Billy is not named in the text of Egan’s book but he is just visible in a Cruikshank engraving illustrating the book. The play ran for over 300 nights, breaking a 62 night record held since 1728. Its success spawned multiple dramatizations of Egan’s book that were performed on London and provincial stages. But the play caused Billy Waters' demise. Those who could see him impersonated on the stage no longer felt obligated to pay for his performances on the street, and in March 1823, Billy died impoverished, having pawned his fiddle. His dying words were reportedly "Cuss him, dam Tommy Jerry." At his death, Billy was known as King of the Beggars--a title claimed by no-one since.

There was voracious demand for images from Life in London, and varied simple engravings adorned inexpensive street publications. A woodcut by the printer James Catnach shows Billy Waters with a dog. Any one of these many printed images may have inspired the pearlware figures that mimic Billy.

What of this Fabulous Figure itself? It is pearlware and can be attributed to the Enoch Wood manufactory because shards matching it were excavated in the Enoch Wood stash found beneath Burslem Old Town Hall in 1938. The figure has the letter H impressed beneath. I have noticed varied letters impressed on other figures attributable to Enoch Wood. What do they mean? I have no idea!

- Look at how Billy's peg leg is attached to his limb. Although Billy had a below the knee amputation, the peg is not worn against the end of his limb. Instead, he rests his knee on the peg, and the rest of his lower leg is folded to the rear. Not quite like would happen today.

- Another model of Billy Waters was made, probably by some other manufactory. It is smaller and has a dog on the base. Always sweet to have a dog, but the figure is significantly smaller—more like 6-1/2” high, rather than 8”. The height difference makes a major difference in footprint, and the smaller figure just does not have the presence of the Enoch Wood model.

- Sometimes you will find Billy Waters with a white face. Shortage of black paint that day? Who knows! I have only recorded a white face on the small figure.

- The figure occurs titled--again, in the smaller version only, I believe.

- Watch for reproductions, titled usually, that are all over the internet.

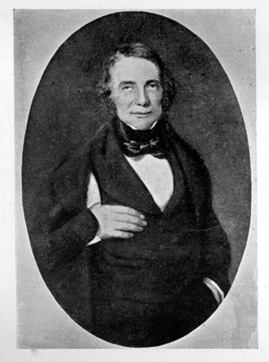

Enoch Wood, John Liston in the role of Van Dunder

This wonderful pearlware figure depicting John Liston in the role of Van Dunder was made by Enoch Wood from circa 1825. It is 7-1/4” high. This example is in dazzlingly perfect condition. Not a flake anywhere on the black and the glaze is silky soft. The figure matches shards found in the foundation of St Paul’s Church, Burslem, where Enoch Wood placed a time capsule of his wares. But to eliminate any doubt, the figure is impressed WOOD beneath. The letter K is also impressed, and I have noted various other impressed letters on Enoch Wood figures. Their purpose is unknown.

John Liston (1776-1846) starred on the London stage from 1805-1837. He was the comic genius of his time, unequalled in farce. His most memorable role was that of Paul Pry in John Poole’s play of the same name, which debuted at the Haymarket in 1825.

On 18 Sept 1824, Liston debuted in a new role at the Haymarket Theatre. As Van Dunder in John Poole’s ‘Twould Puzzle a Conjuror; or, the Two Peters, Liston portrayed a bumbling Dutch burgomaster charged with determining which of the numerous shipyard workers named 'Pieter' was Peter, Czar of Russia, working in disguise to learn trade secrets. Van Dunder wore baggy Dutch bloomers and silly shoes. His catch phrase, the play’s title ‘Twould Puzzle a Conjuror, reflected his dilemma. By the way, this play was a revamp of Poole’s earlier play, The Burgomeister of Sardaam, which had failed at Covent Garden in 1818.

Can there be any doubt that the print alongside the figure was its design source? Look at the pattern on the stockings extending up from the ankles. The scroll is decorated identically, with a red medallion design in the corner, followed by the words ‘To Hans Lubberly Vany(?) Burgo (our potter truncated the text because he had trouble squeezing in all the letters!) Words from the play’s text--Read it indeed! that’s very easily said, read it!!-- are on the base of the figure and on the bottom line of the print text.

The British Museum Catalogue describes this print as a hand-coloured lithograph of Mr. Liston as Van Dunder in ‘Twould puzzle a Conjuror, lettered with the title, followed by a line as spoken in the part, signed in the image with the unidentified monogram GEM, date 1825-1835.

I have recorded a Staffordshire figure of Van Dunder from the same figure molds used for this figure, but with minimal enamel painting (no stockings, no decoration on the column behind, no wording on the base or scroll) and standing on a white base with a red line around it. It lacks the crisp, animated modeling and delicious glaze apparent on this month’s Fabulous Figure. A factory second? A practice piece? We just don’t know.

For the record, Halfpenny describes this figure as Liston in the role of Lubin Log in Love, Law, and Physic. Clearly an error that others have unfortunately perpetuated.

Tree Grafter and Companion

Staffordshire figure pair of a tree grafter and his companion. Enamel-painted pearlware. Circa 1815. H: 8".

Bocage figures don't get much finer than this. A picture is worth a thousand words, so what more is there for me to say? This pair, the tree grafter and his lady companion, are uncommon--besides this particular pair, I have seen no other with intact bocages. And just look at how broad and beautiful those bocages are! Clearly, figures of this form invite damage, and both are more commonly found with little or no original bocage. The companion's outstretched arm is also particularly vulnerable. So what do we normally see here? Mentally remove the bocages and the lady's arm, knock the figures about a bit, separate them so you have only a single rather than a pair--and that is what usually comes to market.

This pair of figures is in original condition with the only restoration being to the lady's hand. The glaze and enamels are superb. Although these figures have a Walton-type bocage, there is no reason to believe Walton made them. This bocage was rather generic and several potbanks used it. But other features link these figures to a potbank that a friend of mine has dubbed Too Good To Be Walton (TGTBW). The TGTBW potbank, true name unknown, made a range of figures with distinctive features, some of which appear on our figures shown here. Interestingly, I have repeatedly noted a slight mismatch in the colors of the bases of paired figures from TGTBW. I believe that a different placement in the muffle kiln used for the enamel firing would account for this. Those few degrees difference in temperature was all it took. Also, slight differences in the 'fru-frus' on the base make me think that different hands assembled them--but that is how things were done then. However, the figures are very clearly a pair and have lived together for around two centuries. Amazing, aren't they? The bocage leaves are as chunkily crisp as pastry cut-outs; the modeling is superb; the shredded clay decoration on the bases is so fine, but above all the enamels and glazes just glow.

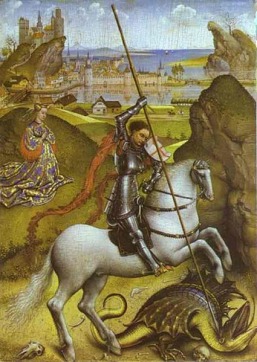

Wood & Caldwell St. George and the Dragon

St. George and the Dragon. Enamel painted pearlware. H: 11.12" (excluding spear). Made by Wood and Caldwell of Burslem, Staffordshire, between 1805 and 1818.

This dramatic St. George and the Dragon is recognizably the output of the Wood & Caldwell partnership that operated in Burslem from 1790 to 1818. The figure bears traces of the Wood & Caldwell mark on the reverse. We can date the figure to between 1805 and 1818. The reason: silver lustre (it used platinum and you can see it on St. George's helmet and shield) was first used in 1805, so the figure can't predate 1805; and as Wood & Caldwell dissolved their partnership in July 1818, the figure had to have been made some time before July 1818. This is my very favorite Wood and Caldwell figure. This partnership was not renowned for it's animated modeling, but this figure is an exception. There is so much Power here: St. George lunging, the horse shying, the dragon rearing. Isn't the horse just bee-you-tiful?? And the colors are stunning--just look!--even the silver lustring has a lovely patina and is largely unworn.

Who was St. George? You probably know that he was England's patron saint. But you may not know that Saint George never set foot in England. In fact, he may never have existed! There are no historical sources for his existence; rather his origins are hagiographical. But by the second millennium, he was well established in European culture and was to become a recurrent figure in the iconography of many nations. A popular medieval book of hagiographies written between 1260 and 1275 by Jacobus de Voragine tells the story of Saint George and the dragon. By those times, the dragon symbolized Satan and embodied the evil and paganism that the Christian Crusaders believed they were fighting. According to the tale, a beautiful princess was about to be sacrificed to an evil dragon, but Saint George, after making the sign of the cross, stayed (not slayed!) the dragon with his lance— this is the pose in which he is traditionally shown. During the Crusade, soldiers revered Saint George and adopted his red and white cross as their own. From the thirteenth century, he was gradually accepted as the patron saint of England and his cross was adopted as England’s flag and it remains so today, although other entities too claim Saint George and his flag as their own.

Fascinating Factoids.

1. According to Wikipedia: "St. George is the patron saint of Aragon, Catalonia, England, Ethiopia, Georgia, Greece, Palestine, Portugal, and Russia, as well as the cities of Amersfoort, Beirut, Bteghrine, Cáceres, Ferrara, Freiburg, Genoa, Ljubljana, Gozo, Pomorie, Qormi, Lod and Moscow, as well as a wide range of professions, organisations and disease sufferers." If you have a need for a patron saint to stay or slay the dragons in your life, I sure St. George could accommodate your needs too!

2. Wood & Caldwell were not the only Staffordshire potters to model St. George and his famed dragon. Others had a go at it too, and figures are found decorated in underglaze colors and colored glazes. Some models are positioned on a plinth. Of course the enamel painted versions are my favorites--and the silver lustring must not be worn away. Such figures impart a dazzling brilliance to a mythical event.

3. The spear that St. George holds is always a replacement. I think the original was probably metal. I made this one from a bamboo knitting needle, which I painted. If you have a St. George and he lacks a spear, please make him one too. You never know when he will need it...no, seriously, the figure just looks so flawed without it.

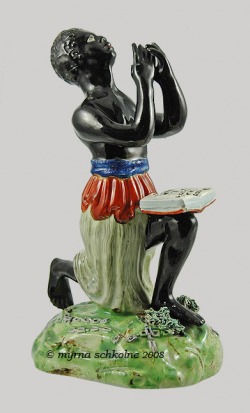

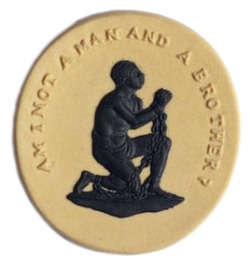

Kneeling Freed Slave

Emancipated slave. Enamel painted pearlware. H: 7". Made in Staffordshire circa 1810.

In May 1807, the British slave trade was abolished and in the 1830s slavery was abolished in all Britain’s colonies. The open book on the slave’s knee reads BLESS GOD THANK BRITTON ME NO SLAVE. Many potters were barely literate, so Britain is spelled "Staffordshire style!"

|

In 1787, William Hackwood, working for Wedgwood, designed a seal for the London committee of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It depicted a shackled, kneeling slave, hands clasped as if in prayer, and the motto AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER? For the next forty years, metal and ceramic artifacts bearing the symbol of a kneeling slave (such as this Wedgwood medallion) were to be fashionable symbols of the abolitionist cause. Did Hackwood's design inspire the design of this figure group? Despite the similarity, I believe this figure has some other source....but I can't find it. If you know, please tell me. |