When I was photographing for my book due out later this year, I came across a pair of figures of Neptune and Venus in a private collection. The figures stood on tall plinth bases and had NEPTUNE and VENUS impressed on the back of each plinth in tiny upper case letters. I associate that type of titling with Ralph Wedgwood, but the figures seemed a little too fine to be Wedgwood's work....although, in fairness, he could pull it off sometimes! The figures were very like the pair below that I came across just this week. Fine old figure pairs like this are as scarce as hen's teeth, so I was pleased to see this pair. The picture doesn't do them justice, but you get the drift. Interestingly, this time I am told that only Venus is titled, again with small uppercase letters impressed on the reverse of her plinth. These figures are probably circa 1800.

|

Last week we looked at Time Clipping the Wings of Love, and this week Venus has my attention. Sounds like an early start on Valentine's day, does it not? But before I go there, I want to tell you that this year's New York Ceramics Fair was to die for. The ceramics were simply breathtaking. As always, Reggie Darling and Boy were there--what would the fair be without them?--and they have done the event justice in this week's blog. So click here to read all about it! When I was photographing for my book due out later this year, I came across a pair of figures of Neptune and Venus in a private collection. The figures stood on tall plinth bases and had NEPTUNE and VENUS impressed on the back of each plinth in tiny upper case letters. I associate that type of titling with Ralph Wedgwood, but the figures seemed a little too fine to be Wedgwood's work....although, in fairness, he could pull it off sometimes! The figures were very like the pair below that I came across just this week. Fine old figure pairs like this are as scarce as hen's teeth, so I was pleased to see this pair. The picture doesn't do them justice, but you get the drift. Interestingly, this time I am told that only Venus is titled, again with small uppercase letters impressed on the reverse of her plinth. These figures are probably circa 1800. Below we have another pair of Venus and Neptune, from John Howard's archive. These figures are a little later, perhaps 15 to 25 years later, but they are stlll quite definitely early figures. They are after Derby porcelain models. Although very pretty and correct, I must admit that they are not my favorites. On the other hand, I really like the "Sherratt" Neptune and Venus that you see below. They have a quirkiness that the Derby-style pair lack. And of course Cupid alongside Venus is a lovely addition. If you are ever considering a pair of these, be sure that Cupid is in place. I have seen several Venus figures that have lost the Cupid, and if you didn't know to look for it you might not miss it! Below is another pair of "Sherratt" Neptune and Venus figures, courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. I just love these bases. Can you notice something different about this Venus? Look carefully at her head. The two "Sherratt" Venus's have different heads. Both are correct, as "Sherratt" did indeed make two models of Venus, differing in only the head. And to prove my point that Ralph Wedgwood could, at times, really excel, I leave you with this 29.4 inch figure of Venus impressed WEDGWOOD. Is she not a stunner??? Photo courtesy of Skinner.

0 Comments

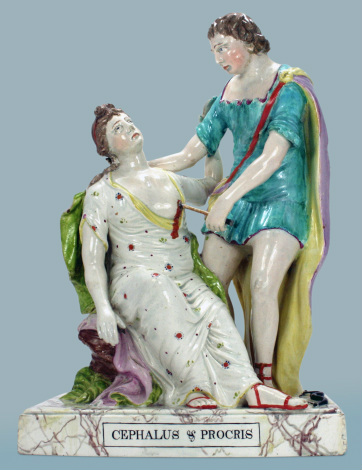

This figure group, courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, portrays Time Clipping the Wings of Love . It is after an earlier Derby group, which, in turn is after James Macardell’s mezzotint of Van Dyck’s sixteenth-century painting. Is that a mouthful?  This is a print of the painting that started it all, and you can see that the figures are positioned rather differently in the earthenware group. I do think the earthenware group is lovely. Cupid, of course, symbolizes love. Note the skull and cross bones on the base...the death of Love! The group is in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, and I share their photo with you. The Museum object record attributes the figure to Ralph Wood II or Ralph Wood III. Stop agonizing, Fitzwilliam. Fret no further as to which Ralph Wood you should choose. Neither one made this figure. Instead, it was quite definitely made by Lakin and Poole. The marbled base that the figure rests on supports the attribution. Yes, other potters also used marbled bases....but the very subtle marbled painting is not like that used by others. And here comes the big clue. Look at the recessed edge running all around the top edge of the base. This ties down the attribution to Lakin & Poole (active 1791-1795). This distinctive marbled base-with-recessed-edge occurs again and again on Lakin & Poole figures with larger bases. Below is an example of Cephalus & Procris. This example is marked "Lakin & Poole". There is another just like it in the Fitzwilliam collection. This time the online object record states the maker is Lakin & Poole....but I am not sure if the object is actually marked or if the museum has attributed it, correctly this time. The Fitzwilliam has at least 4 Lakin & Poole figures on bases just like the two we see above. Amazing that after a century or so of owning these figures nobody has made the connection that would attribute Time Clipping the Wings of Love to the correct pot bank. But don't let that stop you looking at the site some time. I love, love, love the collection, even if the web site does take determination to navigate. I am very grateful to the Fitzwilliam and other museums that put their collections into cyberspace, but this in no way reduces my extreme frustration at errors in object records. I worry that these errors, once in cyberspace, will spread erroneous beliefs. We all make mistakes, so how do we set museum records straight? Should we write to museums? Ha! I have tried that. I can no longer look at the Winterthur site lest my eye yet again hit the figure randomly attributed to Walton--despite my corresponding with the museum about it over a year ago.

The bottom line is that we have to record our knowledge correctly if we are to learn. That's why I hold museums, the care takers of our treasures and the sharers of knowledge, to the highest standards. If you are ever misguided enough to bequeath a figure to a museum, please make sure it will be displayed PERMANENTLY and described CORRECTLY. Better yet, let it go back onto the market. Remember, remember: this is the week for the NY Ceramics Fair. If you are going to be there on Tues, Wed, or Thurs, and would like to meet, email me...and enjoy! It takes more than a village to delve into early figures. It takes the whole world, and, thanks to the Internet, that is now possible. A gentleman in Portugal emailed me this week and filled me in on this figure of the Madonna below. This example is in the Willett Collection, Brighton and Hove Museums. N.S. DOBOM DESPACHO. What does that title mean? I am only smart enough to know that the wording is not Latin. I suspected it was Portuguese, but I didn't know how to translate it. None of my Catholic friends was helpful, but at last, we have the answer! The title should read N.S. Do Bom Despacho. It translates as Our Lady of Good Delivery. the N.S. standing for "Nossa Senhora." Now here is the really interesting part. There is a hole atop the figure's head. I always assumed this was intended to hold a metal halo. Not so. A metal crown would have fitted into it. The story behind the crown is particular to Portugal. In 1646, after his coronation Portugal’s new king, King John IV (Dom João IV) gave his crown to the madonna, saying she was the true queen of Portugal. Thereafter, Portugal’s sovereigns had acclamations instead of coronations, and they no longer wore crowns. BTW, Portugal’s monarchy ended in 1910. But the story does not end there. The collector in Portugal went on to tell me that his figure has baby Jesus holding a small blue ball in his hands. This is a globe, signifying the universe. Well, there simply isn't a ball in the figure above. Possibly there is some damage, but probably there never was a ball. But here is a close-up of the unpainted figure in the Potteries Museum....and baby Jesus, although now headless, does indeed clutch a globe. This figure was excavated from the Burslem Old Town Hall site associated with Enoch Wood, and it is impressed "28" beneath. Figures in that cache date from the 1820-1830 era, so that helps us date our madonna with relative accuracy. While we are looking at this figure, one other point needs to be made. A collector contacted me about this very figure, noting that the faces of the madonna and child are very square. I have pointed out in the past that John Dale's figures have obviously square faces, and he wondered if John Dale made this madonna too. No, no, no. Yes, nearly all John Dale figures have squarish faces....scroll down to the blog posting on the Sacrifice at Lystra to see it again and again. But John Dale did not have the monopoly on square faces. Other potters also sometimes made figures with square faces. When everything else adds up to confirm a Dale attribution, a square face is simply the cherry on the top. Alone, it means nothing, You may recall a blog posting that included a very rare mermaid figure a year or two ago. Here she is again. Now, thanks to Google books that has digitized so much ancient material, I was able to link this figure to the past, thereby dating it with some precision.

In 1822, there was still widespread belief in mermaids. After all, credible sources reported sightings, so why not believe? In that year, London was excited when a mermaid went on display. This grotesque shriveled creature was almost three feet long and it had been constructed from a monkey's upper body attached to a big fish tail. An American whaler captain, duped into believing he had found a rare and valuable treasure, had sold his ship for $6,000 to fund his purchase. When it went on show in London, naturalists quickly deduced that was "a composition; a most ingenious one, we grant, but still nothing beyond the admirably put together members of various animals.” Nonetheless, each day hundreds of people paid to see this disgusting object. I believe that Staffordshire mermaids date from this period. Perhaps the quick exposure of the hoax ended the manufacture of earthenware mermaids, because only three are known. Again, thanks to the Internet, I learned that the mermaid of 1822 resurfaced in America in 1842. The great American showman P.T Barnum, then at the start of his career, acquired this famous fake and presented it cloaked in scientific knowledge as “The Feejee Mermaid.” The publicity stunt stirred much debate and controversy about the existence of the legendary mermaid. The Internet has not yet revealed why the Staffordshire mermaid has wings. Do you know???? PS: The mermaid has a square face, but there is no basis for attributing her to John Dale! I am quite convinced that the majority of earthenware equestrian figures link to the circus. These figure portray early circus stars. The circus was born in the latter half of the eighteenth century, and it was not the circus we know today. Instead, it was all about trick horse-riding. Horses and riders were its stars--the elephants, lions, etc. that we associate with today's circus came much later. This equestrian figure of a Cossack soldier has just leaped out of John Shepherd's stock. Why should Staffordshire potters make a figure of a Cossack?? Of what possible interest was this to Britain's better classes? The answer leads us straight to the circus. In November 1807, The Brave Cossack; or Perfidy Punished debuted on the stage of Astley’s circus, and that production was restaged in March 1812. The goings-on in Europe made Cossack soldiers particularly topical in 1807 and 1812. Cossack soldiers were renowned infantrymen and they fought alongside the Russian army in the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). In 1807, Napoleon’s army advanced on Russia and prevailed in battle. In 1812, Czar Alexander’s offensive against the French was a decisive turning point in the Napoleonic Wars. The campaigns of 1807 and 1812 correspond with the production of The Brave Cossack on Astley’s stage in those years, and this figure was probably made at around the same time. The figure is really rare. I have one or two other examples on file--including a silver lustre example--but I have never seen the figure in the flesh. Another equestrian figure that can also be linked to the circus has also sold from John Shepherd's stock (at Hiscock and Shepherd). This little toper astride a horse probably portrays a circus clown. Around 1768, Philip Astley, the founder of the circus, conceived the first circus clown act with Billy Buttons, or the Tailor’s Ride to Brentford. This comic routine featured a tailor who could not ride but attempted to go by horse to Brentford. The buffoonery of his struggle to mount and stay astride his galloping beast made Billy Buttons a circus favorite. As the circus evolved, its repertoire expanded to include more clown acts. I wouldn't bet on this being Billy Buttons, but it certainly is one or other of the circus clown routines. Again, this is a rare figure and I have not seen another like it.

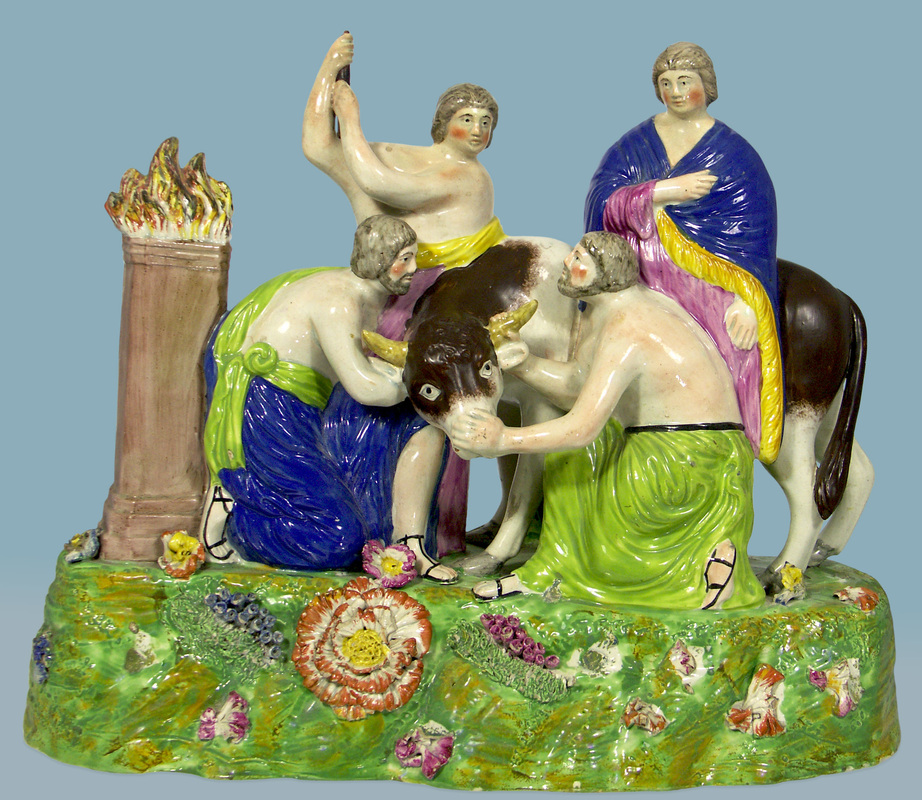

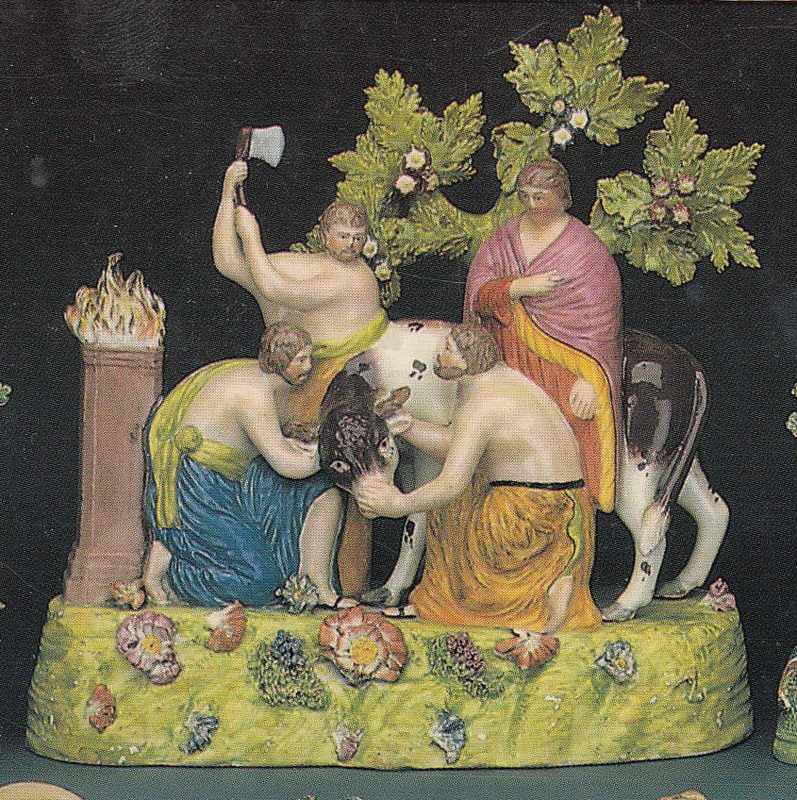

I am amused when I am described as an "expert" because I know I am a perpetual student. And so it was with this figure, which is pictured in my last book. In 2006, I described this figure as The Return of the Prodigal Son. It had traditionally been called that by others. No excuse for me to jump off the cliff behind the other sheep, but I did. In my defense, does the title not fit the figure?....the slaughter of the fatted calf as the prodigal son returns. Fast forward to 2012, and I know better. The figure instead portrays the Sacrifice at Lystra. The New Testament (Acts 14:8–18) tells that when Paul and Barnabas visit Lystra, Paul heals a crippled man. The Lystrans believe the two apostles are Greek gods, and, to their horror, bring out bulls to sacrifice to them. Rafael’s sixteenth-century cartoon portraying the scene (commissioned for a tapestry for the Sistine Chapel) is the design source for the figure group. A similar Roman relief panel (now in the Louvre) showing preparation for the sacrifice at Lystra may have inspired Rafael’s work. Below is a 19th century bible engraving, and I suspect our potter used a similar one as a design source. This rare group is known from three very similar examples. In all cases, the bocage was made separately to fit into a socket, in the manner in which a candle fits into a candlestick. In the example above, the bocage is lost. Here is another from a Christies 1992 catalogue, with the bocage in place. I am confident that John Dale made Sacrifice at Lystra groups. Dale liked socket bocages, and they occur on other figures that link to him. This base with these flowers is found on other Dale examples, as are bocage leaves of this form. Notice the figures' very square faces. Dale faces look like this. And lastly, that very bright apple green on the base is another indication of a Dale origin. Together these features establish the attribution.

My thanks to Stephen Duckworth, whose specialty is Victorian religious figures, for correctly identifying this figure group. |

Archives

February 2024

All material on this website is protected by copyright law. You may link to this site from your site, but please contact Myrna if you wish to reproduce any of this material elsewhere. |