Who made them? I don't know. Interestingly, the bocages are unpainted on the rear. I have recorded two other similar pairs, each made by a different potbank. Here is the second example.

|

Thought you might enjoy this pair of figures. Aren't they simply charming? They embody everything that Staffordshire is about. Yes, they are a true pair, despite the different flowers on each bocage. They were made thus and have lived side by side for around two centuries. Each figure is about 4" tall and sits comfortably on the palm of the hand. Who made them? I don't know. Interestingly, the bocages are unpainted on the rear. I have recorded two other similar pairs, each made by a different potbank. Here is the second example. So which do you prefer? It's OK to like them equally. I do. The third pairing you can see in my book, p.239. Those figures both bear the impressed mark of John Dale. They live on either side of the Atlantic, in two different collections. Hunt for them on the page of marked Dale figures on this site by going to the drop-down MAKERS menu at the top of this page.

0 Comments

Instead of my usual blog entry--these happen every four days--I am going to direct you to some of the other work I have put up elsewhere on this site.

In the 1800s, a prosperous Brighton gentleman, a brewer by trade, named Henry Willett formed a collection of predominantly pre-Victorian English pottery. The heart of the collection was history, and in particular social history. Mr. Willett chose objects because of "the human interest each object represents." What is more engaging and interesting than a figure? Mr. Willett's collection abounded with figures showing both important people and ordinary people going about their daily activities. "The history of the country may to a large extent be traced on its homely pottery" he wrote--and Mr. Willett's large collection remains the ultimate visual representation of English life in the pre-Victorian era. So what happened to the collection? Well, back then, it wasn't considered very grand. The Victoria and Albert Museum exhibited it at its Bethnal Green Branch, so poor people might enjoy it. Everyday life was probably not for affluent visitors to the main museum location, and I believe the V&A declined the collection. So Mr. WIllett founded the Brighton Museum and gave his collection to that institution, and it remains there to this day. Objects in museums are often just stray objects being warehoused. On the other hand, the Willett Collection is the heart of the Brighton Museum. It is prominently displayed, and it has been unsullied by the addition of sundry other objects. Its theme remains powerful and pertinent, and when you tear yourself away you realize you didn't just look at shelves of ceramics. You peeped into the past, courtesy of Mr. Willett. Today we look at three figures that are not from the Willett Collection, but they too give us a glimpse of a long-forgotten past. These three pearlware figures range in height from about 3" to 8" and they all represent Turks. An unlikely subject for a Staffordshire figure, you may think, but exotically attired entertainers, complete with robes and turbans, were commonplace sights at England's fairs, theatres, and shows in the pre-Victorian era. Their existence could so easily be forgotten, were it not for these Staffordshire mementos.

A couple of years ago (was it 2008?), an unusual pair of figures came up for auction in the UK: a small cat and mouse. How I yearned to own them! I had never seen an early Staffordshire mouse and none had been recorded. But the condition report indicated that the back half of the mouse--the half with the cute twisty tail--was significantly restored. I just didn't want to look at that tail and forever wonder how it really should have looked. I passed. To be honest, I wouldn't have prevailed at auction because the pair went for a lot of money, crossing over the GBP1,000 threshold. Hmm....I was surprised. Fast forward a while, and I came across a beautiful little pearlware mouse. Perfect, right down to the tip of its tail. Here comes the good part: the owner thought it was a particularly ugly cat and wanted just over $100. I was delighted. For once, things had gone right. I subsequently saw another mouse in the stock of John Howard. A sweet little thing, it jumped quickly off his shelf into the arms of a buyer. So what happened to the cat-and-mouse pair I passed on? They went into the stock of Sampson Horne and featured in Jonathan Horne's last Exhibition catalogue in 2009. That honor was justified for they are rare little gems. Jonathan knew a rarity when he saw it. Sadly, the pair again came to auction early this year when Sampson Horne's stock was dispersed. This time the condition report was thorough and the mouse had apparently had an even rougher life than I had thought! Didn't stop a buyer paying over GBP2,000 for the pair. So what happened to my lone mouse? I am pleased to tell you my story had a happy ending. I found the cat that paired with it. Now what are the chances of that happening? Almost zero....which is why I sometimes think there is a Pottery God looking out for us collectors. Here they are. My ruler is nowhere to be found, but each is under 3" long. The bases are formed identically beneath so I am sure they are from the same potbank, and they look as if they were painted at the same time. The mouse sits on a longer base....but how else to accommodate that tail? In fact the mouse's nose actually peeps over the front edge of the base, a sweet touch.

FYI, my cat has been reattached to its base, but I am very tolerant of such repair because all the orginal material is there. The only other issues were base and ear chips. A dog fight? We will never know. Those of you who followed the story of the eBay faker who overpainted luster plaques to make them more marketable must read the update on Stephen Smith's amazing site devoted to plaques. Even if you are not a plaque person, you will be fascinated by the lengths this faker will go to purely to deceive. His handiwork reduces the value of plaques, but he just can't help himself. I just can't help myself either: although eBay does nothing, I persist in reporting these items. And Stephen is indefatigable! Thanks Stephen for trying to keep the ceramics market on track. Read all about it here

A few years back, these pre-Victorian figures sold in the UK. The Victoria and Albert Museum has a particularly nice example of the same figure form in its collection. The person with riding crop and breeches is actually a woman, the actress Maria Foote. She was loved for her role as "The Little Jockey" in Youth, Love, & Folly, a comic opera in two acts, authored by William Dimond and Michael Kelly. The play debuted at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, circa 1805. Notable for the role of a female actress disguised as a jockey named Arinette, the play was subsequently dubbed The Little Jockey, and appeared on many provincial stages. Staffordshire potters captured Maria Foote in her most popular role in the early decades of the 19th century. Similar Staffordshire figures continued to be made into the early Victorian period--probably intended to portray the role rather than the actress because Maria Foote retired from the stage in 1831. There are also Derby porcelain look-alikes of the figure, but I like to think our Staffordshire potters were the first to pay tribute to one of the most popular actresses of their day.

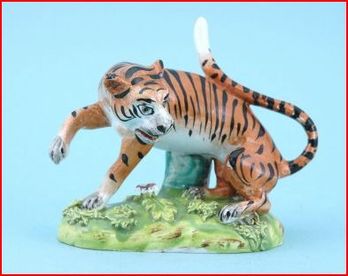

Fascinating Factoids. Maria Foote was born into a theatrical family in 1798. She debuted on the London stage in 1814. In 1821 and 1824, she bore children to Colonel Berkeley, who had promised her he would marry her when issues resolving his inheritance were resolved, but in 1824 it was apparent that was not to be and their association ended. Around that time, Jospeph Hayne proposed marriage to Miss Foote. This very indecisive young man left her standing at the altar not once but twice. Thereafter, she sued him for GPB20,000 for breach of contract, The case was heard in December 1824, but when it became apparent that Miss Foote had initially concealed from Mr. Hayne both her relationship with Colonel Berkeley and her second pregnancy, the jury awarded her a mere GBP3000, most of which went to her attorneys…some things never change! But, like today’s actresses, Maria Foote had a way of landing on both feet. She had been poorly parented, so she was pitied rather than blamed, and public outpouring for her was immense. A February 1825 benefit for her at the Covent Garden Theatre was packed. Maria Foote ultimately went a long way from her rather sordid beginnings. Her theatrical career ended on 11 March 1831, and the next month she married Charles Stanhope, fourth earl of Harrington, thereby becoming the Countess of Harrington. She died on 27 December 1867. Have you seen this fabulous feline on John Howard's site? My first thought: why is there a stump under the leopard yet there is no bocage above? Some figures are made thus, but in most cases a stump is the remains of a bocage. When the bocage breaks, a restorer rounds off the edge to create a naturalistic stump. My second thought: why is the stump a different shade of green? Typically, a bocage trunk, if green, uses the same green as is used elsewhere on the base or on the figure itself. So in my mind things didn't quite add up. BUT John's description said nothing about bocage loss or breakage....and John is totally honest on these issues. So I looked at the picture of the back of the figure. Here it is, also from John's site. Perfection! That clearly is an original stump. Look at how it has been formed to meld into the leopard's body. A one time event? I dug into my archive and found this. Another feline, this time a leopard, formerly in the stock of Andrew Dando. Again, the stump is painted a different green, that same turquoise shade. Why? Does this occur only on felines? Time will tell. I will be watching out for more figures with bocage stumps painted in this way.

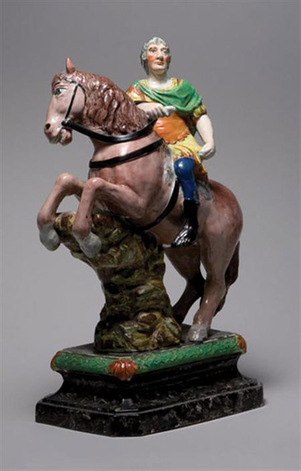

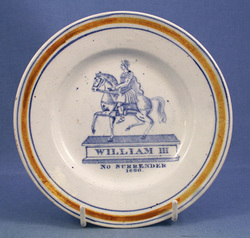

This striking figure, currently in the stock of Earl D. Vandekar, is sometimes found described as King William III, sometimes as the Duke of Cumberland. So which one is it? The confusion may arise because the Duke of Cumberland's name was William. In 1770, an equestrian statue of William, Duke of Cumberland (King George III's brother) was placed in Cavendish Square London. Maybe it looked somewhat like this figure. We don't know because the statue was removed in 1868 and all that remains today is its titled plinth. The other candidate for representation is King William III, who ruled England from 1689 to 1702. It seems unlikely that a long-dead monarch inspired replication in clay, but that is indeed the case, and equestrian statues of William III popped up across England in the 18th and even 19th centuries. William III was a Dutch Protestant placed on the throne by England's parliament in 1689. He defeated his Catholic father-in-law, England's ousted King James II, at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. This victory ensured the end of the Stuart monarchy. It sealed William's claim to the throne and secured a Protestant succession for the British monarchy. The landmark event was celebrated long afterwards. Jacobites attempted to reinstate the Stuarts in the 1700s and anti-Catholic sentiment prevailed in England well into the 19th century.  This pearlware plate, ca. 1800, bears a transfer print of the famous statue. It reads "William III. No Surrender 1690" If you were Protestant, William's victory and accession to the throne was cause for celebration. Dublin erected what was probably the first statue in 1701, and other towns and cities followed. If you were politically astute, you needed a conspicuous display of your family's support of Protestantism. This was the motivation behind Sir William Jolliffe bequeathing £500 for an equestrian statue of William III to be erected in Petersfield, circa 1750. The statue, like those in Kingston upon Hull, Dublin, and Bristol, still stands. Designed by John Cheere, it bears the words "That no testimony might be wanting with how much love and emulation he admired liberty itself, as well as this its celebrated avenger, William Jolliffe, Esq., erected this statue to his memory and placed it in this town."

So why does William III look like Julius Caesar in all the statues? Apparently William led his forces to victory at Namur in 1795, and a medal was struck commemorating the event. The medal shows William III on horseback in Roman dress, a commander's baton in his right hand. The flattering "Caesar theme" was then adopted for statues. The story goes that Petersfield's statue's sculptor committed suicide because of an omission (rumored to be the tongue) in the statue. Next time you see the figure, check for all necessary body parts. Meanwhile, you can ask Paul Vandekar about our fine example in the stock of Earl D. Vandekar of Knightsbridge. Our pearlware figure can reasonably be attributed to Enoch Wood and was probably made while he was in partnership with James Caldwell. I believe the figure dates to the earliest years of the 19thC and was inspired by the statue of William III erected in St James Square, London, ca, 1807. London's statue of William III has beneath the horses hooves a molehill. Why? King William III died from injuries caused when a molehill tripped his horse Thus, supporters of Catholic causes in later years toasted "the little gentleman in the black velvet waistcoat"--the mole! |

Archives

February 2024

All material on this website is protected by copyright law. You may link to this site from your site, but please contact Myrna if you wish to reproduce any of this material elsewhere. |