|

Please note the changes to the site. You may want to follow the "NEWS" page (at the top). This will replace the dealer showcase and it will allow me to post other snippets of information that I want to share.

1 Comment

It's almost time for Andrew Dando's much-awaited Exhibition. Full details here. Enjoy browsing and buying from Andrew and Jan's carefully selected stock.

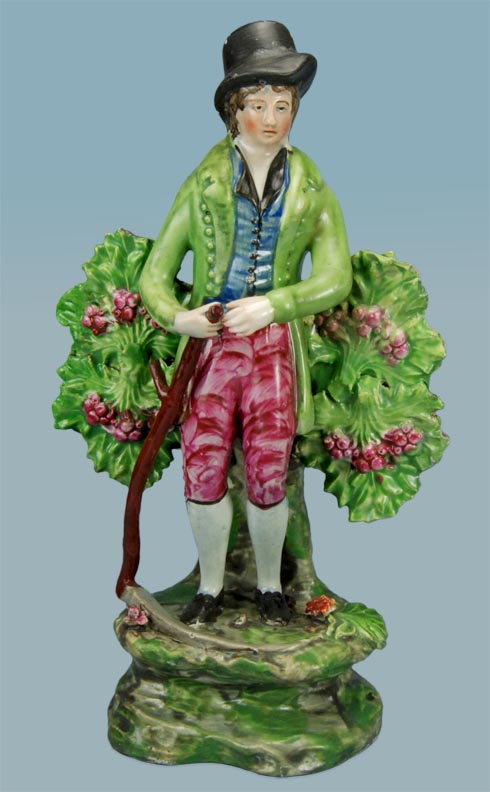

Many of you write to me thinking I only like perfect figures. Not so, not so! I hate shoddily heavily restored figures, but very many figures I own have 'issues"--restoration, damage etc. My rule is that the yummier the figure, the more tolerant I am of "issues." The figures of Falstaff immediately below are, to my mind, particularly boring. I imagine it would take a perfect example with great enamels to make me want to own it. As you may know, the figures depicts Sir John Falstaff, the rotund cowardly knight in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1, and Henry IV, Part 2, and in The Merry Wives of Windsor. Both these figures are impressed "WOOD & CALDWELL." The little leaves and flowers on the bases, and the ochre lines on the right hand base are typical Enoch Wood features. The silver luster on the shield of the right hand figure tells us that it was made after 1805, the year in which silver luster was introduced commercially. Because the figure is marked, we also know it was made before the dissolution of the Wood & Caldwell partnership in 1818. Notice the difference in the hands that hold the sword. That raised hand is very vulnerable to damage and most hands and swords are restored. I suspect that the hilt originally had a guard present, as you can see on the right hand figure.  This Enoch Wood/Wood & Caldwell figure of Falstaff is the most common earthenware depiction of Shakespeare's character. Derby produced a similar porcelain figure, circa 1770, and reissued it in the early 1800s. The Derby figure derives from either the mezzotint or the painting by James McArdell depicting the actor James Quinn as he looked in the role of Sir John Falstaff in 1746 and 1747--and you see it alongside. Clearly the earthenware figure then mimicked the Derby portrayal. Much, much prettier than the Enoch Wood figure of Falstaff is the figure by yet another pot bank. I don't know the name of the pot bank, but you see two examples of that Falstaff below (formerly in the stock of Andrew Dando). To my mind, this is a really lovely figure and I would be happy to own one. Note that the figure is made with the sword arm curved inward to make it less vulnerable. The rarest figure of Falstaff is the little one below. This time, Falstaff is seated.  I think that the engraving alongside, Henry Bunbury's engraving of Falstaff at Justice Shallow's Mustering his Recruits, published in 1792, may have inspired the unusual small seated figure of Falstaff. I await my the perfect knight, and one day I will find just the right figure of Falstaff for my collection. Dear Reader, I approach this topic with trepidation because I fear boring you.....but we REALLY need to start talking about these things, so here goes. Making sense of the vast number of early Staffordshire figures requires sorting them into Groups. Clearly, each Group of figures must have multiple common features--rather like a group of people from the same family. With people, we look for resemblances in eye color, noses, body shapes...but with figures, the most obvious place to start is with the bocage. Each pot bank used its own small range of bocages. Some of the bocages might have been very like those used by neigboring pot banks. Others were specific to only one pot bank.....and these "exclusive" bocages are so helpful in linking figures that share a common origin. In this post, we will be looking at the holly bocage. This is what it looks like on a pair of figures of a mower and a haymaker. Excitingly, only one pot bank used this bocage. What was the potbank called? I have no idea. In her book, Pat Halfpenny notes an array of figures that have bases with blue, red, and white scrolls, and she suggests the name "Patriotic Group" for these figures. Figures with holly bocages can be shown to come from the same very source as the figures with the bases that caught Pat's attention. That means that if you see a holly bocage, you know that the figure belongs to the Patriotic Group. As you can see, the holly bocage is rather splendid. It comprises large leaves, and the berries are integral to each leaf. Whereas flowers are usually added to leaves after they are fashioned, these holly berries are part of the molds used for the leaves. On the fronts of leaves, the berries are typically picked out in red/pink, but on the backs of leaves they are more typically painted green. The Patriotic Group is big. In other words, the unknown potbank that made figures with holly bocages turned out lots and lots of figures-- and it used several different bocages. Here you see our mower and haymaker again....but with different bocages. In this case, each bocage frond comprises one leaflet arranged atop five others. This frond is not exclusive to the Patriotic Group, but it occurs most commonly on Patriotic Group figures. I am confident that Patriotic Group made this pair of figures too. The turquoise palette and the painting style are all consistent with a Patriotic Group attribution. This family group below also has a holly bocage, and I am certain this happy family can also be attributed to the Patriotic Group. Again, we find this group made with other bocages also associated with the Patriotic Group. As an aside, note the base on the happy family groups. This specific base proves to be exclusive to the Patriotic Group---so you see where knowledge about a bocage can take us! Also, look at the handsome couple. Those figure forms are quite specific to Patriotic Group. That same lady and gentleman occur in a host of other settings--and always with a base, bocage, or some other feature that links to Patriotic Group. Above, we have two figures of the lady. One has the holly bocage. The other has the bocage we noted on on the second mower and hay maker pair above, with one leaflet placed atop five.

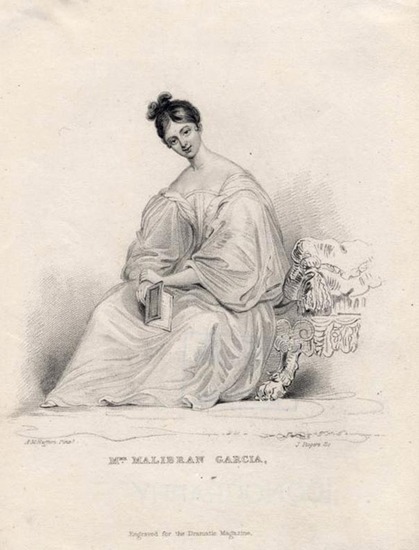

Lest you think the plot ends here, think again. Both figures above have sprigs on their bases that are specific to the Patriotic Group. But that's for another time. The point is that once we start linking figure that share common features, things gel. It doesn't take too long to discover which features are exclusive to a Group--and then we can go about identifying additional figures from that same Group. Victorian Staffordshire figures abound with royalty of all nationalities, but not so the early figures. Kings, queens, and other members of Britain's royal family were rarely captured in clay in the early 1800s. King George III ruled from 1760 to 1820, yet not a single Staffordshire figure portrays him. His son, George IV ruled from 1820 to 1830. His debauched life style and his scandalous marriage kept him very much in the public eye for most of his life, so you would think that figures of him would be plentiful. Alas not. I know of only this one in the Willett Collection, Brighton Museum.  The figure is charming--even if the king was less so. Alongside is a contemporary image of George IV, so you can see the likeness to the figure is quite strong. That puffy hairdo is unmistakable! The dark colors of the print hide the vastness of the king's overindulged body, and the tight coat on the figure was surely an attempt to reign in that mass in the era before spandex. I simply don't know why there are not more figures of King George IV. King William was next on the throne for a few years (1830-1837 ). Again we have no figures of him, although we do have rare busts of William and his queen. Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837. Young, sweet, and oh-so-virtuous, she was quite the opposite of her naughty kingly uncles--but again she was not captured in clay in the early years of her reign. In fact, just one early figure of her is known (photo courtesy of Jonathan Horne). You can see that the crown rests alongside Victoria, so the figure was probably made before her coronation in 1838. Look at all the work that went into the molds for this figure. Are you amazed that more were not made? And is the figure not lovely? It was made by the "Sherratt" pot bank, as evidenced by the distinctive base. Strangely, the figure of the young queen is after this engraving of the actress Maria Malibran that appeared in the Dramatic Magazine. So what is the link between Queen Victoria and Maria Malibran? Well, the figure of Queen Victoria is from the very same molds as were used for a figure of Maria Malibran. Yes, a "Sherratt" figure of just this form but titled MALIBRAN is documented. Maria Malibran (1808–1836), a renowned beauty and a mezzo-soprano of extraordinary vocal range and power, earned international accolades and adoration on the stage. In 1836, Miss Malibran suffered permanent head injuries when falling off a horse. Thereafter, she performed a handful of times before collapsing on the stage in Manchester in September 1836 and dying days later. Maria Malibran died shortly before Victoria came to the throne, so the figure of Malibran was conveniently recycled to portray the young uncrowned queen. Was that not quick thinking on the part of a potter? I know of only two figures of Miss Malibran. One is the "Sherratt" figure titled MALIBRAN previously mentioned. The other is in the Fitzwilliam Museum (the photos below is from the museum's site.) The Fitzwilliam data record describes this figure as a Victorian flatback. First, it is not a flatback. It is beautifully modelled and painted in the round. Secondly, I strongly suspect the figure was made not much later than Maria Malibran's death in 1836, and that would make it pre-Victorian. In any event, it remains a glorious figure with a fascinating link to royalty.

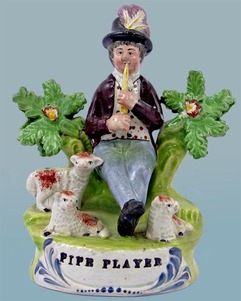

I want you to see some smaller figures that have crossed my path recently. We all should love tiny treasures because they add punch to any collection. The first figure is rather special because it bears the rare TITTENSOR mark. Off the top of my head, this figure is only about 4 inches tall. For a little figure, it is wonderfully crisp, and the glaze is bright. You can see the TITTENSOR mark clearly on the reverse. We associate Tittensor with under-glaze figures, but I have recorded four enamel-painted figures with the Tittensor mark. Three of these have bocages--and the bocages are quite different from the bocages on Tittensor's under-glaze figures. I suspect that enamel-painted figures mark a subsequent phase in Tittensor's potting career. For a long, long time, I have owned this little figure titled GUITAR PLAYER. She was made by John Dale of Burslem and is marked "I. DALE BURSLEM" on the reverse. I was thrilled when I got her. She sits on the palm of my hand, and its as if her whole little world is within my grasp. A fellow collector has owned her companion, titled PIPE PLAYER, for a long time. That yellow staining in the crotch area looks as if this PIPE PLAYER had an accident! Oddly, it is far more apparent in a photo than in real life. In any event, I was delighted when its owner recently parted with this little man. Here they are, reunited at last! Yes, both are marked. Notice the lines of indentations--rather like teeth marks--that you can see on the backs of both bases. Those occur frequently on Dale figures, as do the bright apple-green bases. These bocage flowers are also specific to Dale. I am really thrilled to have completed this pair. A small collecting triumph that gives me much pleasure. Marked figures are always a special thrill, but most of our figures are unmarked, and they can be every bit as delightful. I photographed this couple recently. This homely couple are not dandies. Rather, I think they are simply a courting couple. I haven't seen them before, and what a fascinating glimpse of a bygone era. Peeping into the past with my figures gives me endless pleasure.

|

Archives

February 2024

All material on this website is protected by copyright law. You may link to this site from your site, but please contact Myrna if you wish to reproduce any of this material elsewhere. |