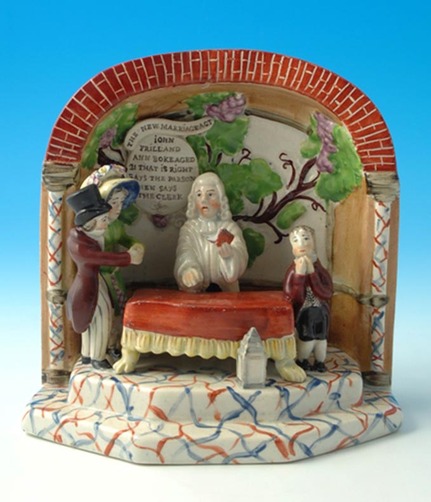

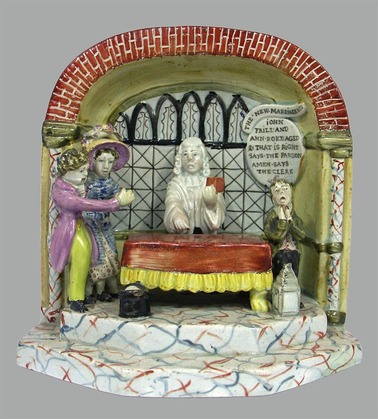

Recently, a collector asked me about a New Marriage Act group, and, although we have explored the topic before and it is thoroughly covered in my book, let's take a quick look at it again. The story behind the group is like this: Prior to 1823, England's marriage law was very demanding and difficult. To get around it, people tended to lie to get married--even though they were then marrying in violation of the law. This usually suited both parties perfectly well--but many years later, either the husband or wife could decide to use the violation to get their marriage anulled. Given that divorce was impossible, an anulment was a convenient way to end the marriage, and it often suited both parties quite well. Sounds OK? Well, it was, but it caused problems for children. When a marriage was anulled, children became illegitimate, and this had disastrous consequences on inheritances.

So what was the solution? Well, the New Marriage Act of 1823 made it no longer possible to anul a marriage because of a petty violation of the law that had occured at the time of marriage. Staffordshire figure potters were quick to see the humor in these situations and they potted various groups commemorating the 1823 legislation.

Below is another example of a New Marriage Act group within an arbor. Notice that the arbor is decorated quite differently--but I think Roger's is prettier. Both these examples were made shortly after 1823. Beware later groups in arbors portraying the same theme. And if you have one, please send me a picture to include in the Reproductions chapter of my new book.

Several of you said nice things about my my much-publicized elephant . The Antiques Road Trip episode aired in the UK this week, and I have been reminded that there are unanswered questions. So here goes. First, why does the elephant have a castle on its back? Well, I wish I knew for certain! The sight was probably somewhat familiar to Londoners, because London was a Mecca for entertainers with exotic animals. In 1679, the scientist Robert Hook noted seeing an elephant carrying a castle and man on its back on London’s streets. Also, a similar motif had been used for centuries in the arms of Coventry and as the emblem of London’s Cutlers’ Company (remember elephant tusks supplied ivory for the handles of knives--hence the appropriateness of the motif for cutlers.)

But elephants were very much in the news in the 1820s. Chunnee, a famous elephant in London's Exeter Change menagerie, was killed horrifically in 1825, and there was much outrage. Chunnee was a much-loved London attraction, but after years of captivity within a menagerie cage, he had had enough. And as he matured sexually, he became more difficult to control. Each year, his keepers administered increasingly powerful laxatives, which were thought to control his libido! In 1826, Chunee, then about twenty-two years old, was so enraged by his seclusion (and the laxatives, no doubt) that it was feared he would reduce his prison to rubble and liberate his ferocious fellow inmates. It was decided that Chunee had to be killed. This was easier said than done, and it took three agonizing days. Poison failed, as did a blundering firing squad. Finally, within an hour a single cannon fired 152 musket balls; Chunee fell and was dispatched with a sword-thrust. But even dead, Chunee remained a huge problem: what was to be done with a five-ton, rapidly decomposing cadaver? The menagerie’s carnivorous animals could make but a small dent in Chunee’s remains, and so the body was removed piecemeal, with much mess, difficulty, and publicity. The Mirror reported that two large steaks from Chunee’s rump were broiled and eaten by those dismantling his corpse. Noting that stewed elephant’s foot was a delicacy, the magazine provided its readers with a recipe!

Perhaps Chunnee’s fame or his horrific death in 1825 created a demand for my figure. Or possibly the elephant act at Astley’s Circus in 1828, or the elephant celebrity starring on the London stage in The Elephant of Siam from 1829 made the model popular. And it is possible that the castellated elephant on menagerie show cloths possibly inspired my figure. Will we ever really know?

And as a last image, I thought you might like a close-up of the little man astride my elephant. He seems to have been forgotten amidst the discussion of all else. But is he not too adorable? I am surprised the molds were not used to make him as a separate figure also.....but perhaps they were. Let's keep looking!

Elephant and Castle is the name of an area in the south of London. I think the name originally applied to a major traffic circle, which was named for an inn (The Elephant and Castle) that had stood on that very site. I thought you might like a glimpse of the tube station.